First, a few vertebrae scattered at the edge of the sandy arroyo.

My husband and I climbed the bank. There, a jawbone, more scattered bones and, nearby, a pelvis with several vertebrae still attached.

It must have been an elk. It had to have been there a long time; its bones were bleached a pure, eternal white.

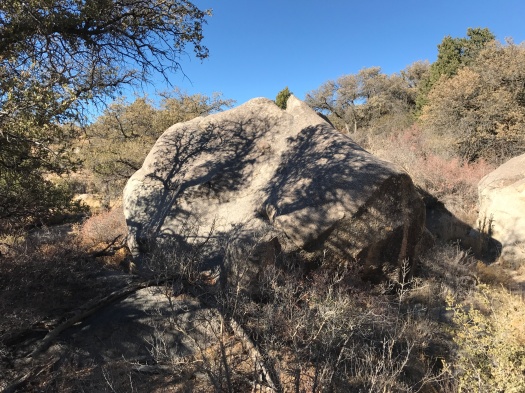

From the arroyo, a steep climb up old jeep trails to the base of Grand Central Mountain and a sweeping view of the Ortiz Mountains.

We didn’t see another soul on our hike, even though it took place at Cerrillos Hills State Park on the day of the “Stuffing Strut,” when the park welcomes folks to its trails to walk off some turkey on the day after Thanksgiving.

Admission to all state parks was free the day after Thanksgiving this year. The parking lot of Cerrillos Hills was full. While others flocked to the marked trails with interpretive signs, we dove into a hike from “60 Hikes Within 60 Miles of Albuquerque.” It uses a complex chain of arroyos, old roads and mining trails that weave between the state park and Bureau of Land Management property to build a killer hike.

It was warm when we did this hike 365 days earlier and warmer this time. The temperature climbed quickly to 70 degrees, and the only shade to be found is in the arroyo at certain times of day or if you tuck yourself carefully under a juniper.

After a rest, we tackled the problem of trying to follow the book’s directions to a “spectacular overlook.” We’d gotten so turned around at this point last year we gave up. My husband and I disagreed about the best way to get there. He’s been finding his way out of arroyos since he was a child. He was right this time, and he’d be right when we disagreed later about the best way to get back to the trailhead.

At the spectacular overlook, we’d be able to see the top of La Bajada, the massive volcanic escarpment, and the glint of sunlight off cars on I-25.

But first, as we navigated a faint, narrow, rocky path to the overlook: we rounded a bend and saw, ahead, the remains of another elk. Ribcage on one side of the trail, pelvis with a few attached vertebrae on the other.

Even a few months earlier, we would have probably have picked up one of the scattered vertebrae we saw Friday in a backpack to take home as a memory of the place.

I’ve walked out of a hike with many a rock, even a few bones. It was the one Leave No Trace practice I fudged. A rock or bone isn’t alive; I didn’t see how taking it with me changed anything, and I loved having a physical reminder of the incredible places I’d been.

But after reading 5280 Magazine’s comprehensive look at how Colorado’s wild places are being loved to death, I saw things differently. The logic I was using to carry home a rock was presumably the same logic people are using when they defecate in the Weminuche Wilderness without bothering to dig a cathole. I don’t condone doing that to the wild world, so I quit doing anything in the wild world that would change it, even in a small way.

What I was seeking by bringing home a rock couldn’t be found, anyway. The experience of being in nature becomes part of you, but as far as what you find there, you literally can’t take it with you. The rock’s meaning only truly exists in its place.

The bones are part of the story of Cerrillos Hills – what’s been and what is still unfolding. Both animals and humans play a role in its story, from the deer tracks at a small spring bubbling up in the arroyo to the capped and abandoned mines in the hills to the train whistle from a nearby railroad.

However those two elk met their end, their bones provide a message to the many other creatures traversing these hills and arroyos daily: Be watchful. Take nothing for granted.

I’m grateful for the chance to read that sentence of the story.

Hike length: 7 miles

Difficulty: moderate

Trail traffic: nope

Wildlife spotted: canyon wrens, crows, butterflies, chipmunk